1 Terminology

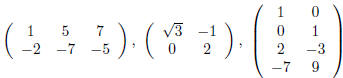

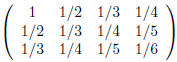

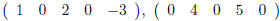

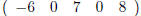

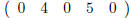

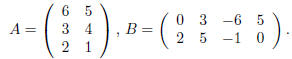

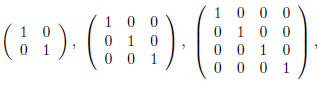

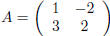

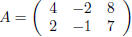

A matrix is a rectangular array of numbers, for example

,or

,or

The numbers in any matrix are called its entries. The

entries of a matrix are organized into rows and

columns, which are simply the horizontal and vertical (resp.) lists of entries

appearing in the matrix. For

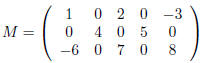

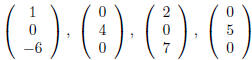

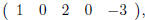

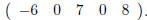

example, if

then the rows of M are  and

and  whereas the

whereas the

columns of M are

,and

,and

.

.

It is worth noting that an m · n matrix will have m rows

with n entries each, and n columns with m entries

each. That is, the number of entries in any row of a matrix is the number of

columns of that matrix, and

vice versa. This is readily apparent in each of the examples above.

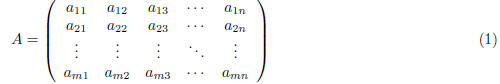

The dimensions of a matrix are the numbers of rows and columns it has. If a

matrix has m rows and n

columns we say that it is an m · n matrix (note that we always list the number

of rows first). So, the first

four matrices above have dimensions  and

and  , respectively. The dimensions of the

matrix

, respectively. The dimensions of the

matrix

M are  An m · n matrix is called square if m

= n. Thus, the only example of a square matrix above

An m · n matrix is called square if m

= n. Thus, the only example of a square matrix above

is the second.

So that we can more easily refer to various entries in matrices, we index the

columns of a matrix from

left to right and the rows from top to bottom. For example, the first column of

M (above) is

the second column is

the third column is

etc. The first row of M is

the second row is

the second row is

and the third row is

and the third row is

We can use this numbering scheme to easily

refer to entries in a matrix: we call the

We can use this numbering scheme to easily

refer to entries in a matrix: we call the

entry located in row i and column j the i, j-entry. For the matrix

the 1, 1-entry is 1, the 3, 2-entry is -1, the 4, 3-entry

is 9 and the 2, 1-entry is -1/6.

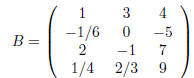

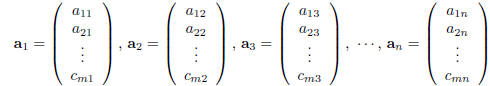

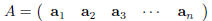

To write down a matrix with variable entries we use variables with subscripts

that indicate their position

in the matrix, using the convention described above. A generic m· n matrix can

therefore be denoted

or just  for

short.

for

short.

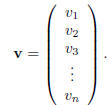

An m ·1 matrix has the form

and is called, appropriately, a column vector. Notice that

since a column vector has only a single column we

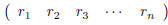

have used only single subscripts to index its entries. Likewise, a 1· n matrix

looks like

and is called a row vector. When we use the word vector

with no qualification we will usually mean a column

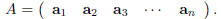

vector. Column vectors give us another shorthand for writing down generic

matrices. Notice that if we use

the matrix A in (1) and set

(i.e. we use the entries in the j-th column of A as the

entries in aj) then we can write

In a similar way one can also use the rows of A to express

A in terms of row vectors, but since we won't be

using this idea later we won't bother to write it out.

2 Scalar multiplication and addition of matrices

Having dispensed with the basic terminology and notation of matrices, we now

turn to how they are ma-

nipulated algebraically . We will see that it is possible to add, subtract and

multiply matrices together, but

only if certain restrictions on their dimensions are met. We begin with the

notion of scalar multiplication.

Given an m · n matrix A = (aij) and a number (scalar) c we define

That is, cA is the matrix obtained by multiplying every

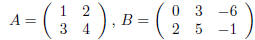

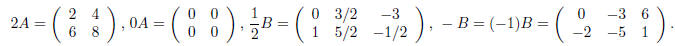

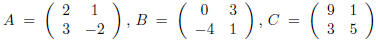

entry of A by c. As examples, if

then

Adding two matrices is also done entry-by-entry. If A =

(aij) and B = (bij) are two m· n matrices, then

their sum is A + B = (aij +bij ). That is, the i, j-entry of A+ B is the sum of the i, j-entries of A and B. It

is important to note that is is only possible to add two matrices if they have

exactly the same dimensions.

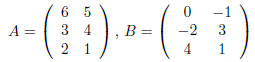

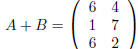

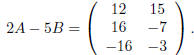

Here's an example: if

then

and

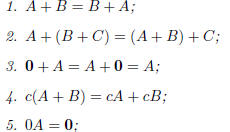

The following theorem summarizes the main · properties of

matrix addition. The proofs of these properties

follow directly from the definitions made so far and are left to the reader. We

will find it useful to be able

to refer to the m· n zero matrix , which is the matrix all of whose entries are

zero.

Theorem ·1. Let A, B and C be m· n matrices, let c be a real number and let

0 denote the m· n zero

matrix. Then

3 Matrix multiplication

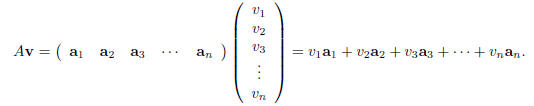

Defining the matrix product is a two step process. First we will define what it

means to multiply a matrix

by a column vector and then we'll use that to tell us how two multiply matrices

in general. Let A be an

m ·n matrix and let v be an· n ·1 column vector (notice that the vector v has as

many entries as A has

columns). Write A in terms of its columns as above,

and write out the entries of v as

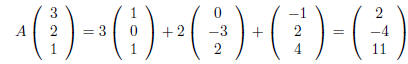

The product of A with v is defined to be

In words, we multiply the columns of A by the respective

entries of v and then add the results together.

According to this definition, the product of an m· n matrix and an· n ·1 column

vector is an m ·1 column

vector, i.e. the product is a column with as many entries as A has rows.

The process of multiplying a matrix by a vector is straightforward enough once

one is used to the

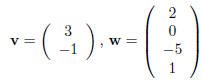

definition. Let's look at some examples. Suppose that we take

The matrix A can only be multiplied by column vectors with

2 entries while B can only be multiplied by by

column vectors with 4 entries. So, if we take

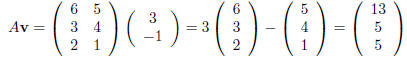

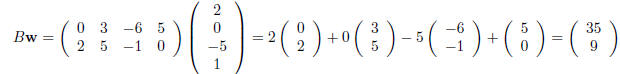

then

and

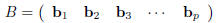

Since we can· now multiply matrices by (suitably sized)

column vectors, we can develop a way to multiply

matrices by other (suitably sized) matrices. Let A be an m· n matrix and let B be

a n ·p matrix. Notice

that B has as many rows as A has columns. In ·particular, the columns of B are n

·1 column vectors and

can therefore individually be multiplied by A. To be more specific, write B in

terms of its columns:

where each bj is an· n ·1 column vector. We define the

product of A and B to be

That is, to multiply two matrices simply multiply the first

matrix by the columns of the second and use the

results as the columns in a new matrix. Since each Aj is an m ·1 column vector,

and there are exactly p of

them, we find that AB is an m · p matrix.

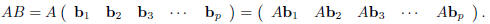

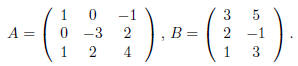

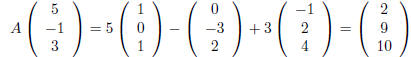

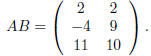

Let's look at a quick example. Take

The product AB makes sense since A has as many columns as

B has rows. The definition of matrix

multiplication says that

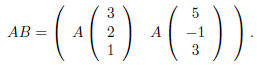

We find that

and

so that

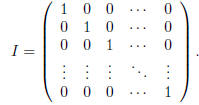

The n· n identity matrix I is the (square) matrix all of

whose entries are zero except for those along the

\main diagonal" which are all equal to 1. Symbolically

The  and

and

identity matrices are then

identity matrices are then

respectively.

The following theorem gives the main ·properties of matrix multiplication. These

all follow directly

from the definitions, but some are harder to prove than others, most notably that

matrix multiplication is

associative.

Theorem 2. Let A be m· n, B and C be n ·p, D be p· q, and let c be a real number.

Then

1. A(B + C) = AB + AC,

2. (B + C)D = BD + CD,

3. (AB)D = A(BD),

4. if I is the m m identity matrix then IA = A,

5. if I is the n· n identity matrix then AI = A,

6. c(AB) = (cA)B = A(cB).

4 Exercises

In exercises 1 and 2, let

and compute each matrix sum or product if it is defined. If

it is not defined, explain why.

Exercise 1.

a. A - B

b. A - 3E

c. 2A + DB

d. AC

Exercise 2.

a. A + CB

b. 3BC - A

c. CAD

d. CA - E

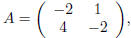

Exercise 3. If  show

that AB ≠ BA but that

show

that AB ≠ BA but that

AC = CA.

Exercise 4. If  construct a nonzero

construct a nonzero

matrix

B (with two distinct columns) so that

matrix

B (with two distinct columns) so that

AB is the zero matrix.

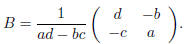

Exercise 5. If A is an· n n matrix, we say the n· n matrix B is the inverse of A

if AB = BA = I,

where I is the n· n identity matrix. Show that if with

with  then the inverse of A is

then the inverse of A is

.

Exercise 6. If  and

and

, use the inverse of A (see the previous

exercise ) to solve

, use the inverse of A (see the previous

exercise ) to solve

the matrix equation Ax = b for x.

Exercise 7. If  find a nonzero vector v so

that Av = 0.

find a nonzero vector v so

that Av = 0.